The conceptual framework of the manual: key concepts

Living Democracy » Textbooks » Living in democracy » Introduction » The conceptual framework of the manual: key conceptsKey concepts in EDC/HRE – tools for the active citizen

By focusing on concepts, this book follows a classic didactic approach to civic and other fields of education. Concepts are drawn from theory, but in teaching and learning they do not create a systematic theoretical framework. Rather, they are selected because they are useful tools for the learner.

Concepts provide cognitive structures that enable learners to integrate new information into a meaningful context and to remember it more easily (constructivist learning). This applies particularly to facts and figures that learners would otherwise have to learn by heart. Concepts also help when reading a newspaper or listening to the news, as an issue becomes significant when linked to a concept such as democracy, power, conflict or responsibility. Concepts are therefore essential in the education of the informed citizen. But they do not only give structure to cognitive learning; they also have implications for the development of values and skills training. These links are demonstrated by all units in this book, as will be shown in more detail below.

Students who have learnt to ask questions guided by key concepts in EDC/HRE will be better equipped to work with new information and new problems in the future (lifelong learning). Concept-based learning also prepares students for more advanced studies at an academic level where they may arrive at the theories that deliver concepts.

How do learners understand and use key concepts?

Thinking and learning has a lot to do with linking the concrete with the abstract. Concepts are abstract, generalised products of analysis and reasoning. Learners can grasp concepts using two approaches, the deductive or the inductive. The deductive approach begins with the concept, presented by a lecture or a text, and then applies it to something concrete, for example, an issue or an experience. The inductive approach moves the other way, beginning with the concrete and proceeding to the abstract. The reader will find that the units in this book generally follow the inductive path.

The key concepts in this book are therefore developed from concrete examples – often stories or case reports. When the students discuss what an example stands for in general, they are asking for a concept that can sum up these generalised aspects. The teacher decides when and how to introduce the concept.

Concepts are tools of understanding that learners can apply to new topics. The more often they use a concept, the better they will understand it, and the closer the links and cross-connections (cognitive structures) will become. Rather than learning isolated facts by heart, learners may link new information to the framework of understanding that they have already developed.

How can this manual be adapted?

The units describe the first of two important steps of learning, moving from the concrete to the abstract. They supply the tools and leave it to the teachers and students to decide how to use them. This is the second step from the abstract back to the concrete. It is not only the needs and interests of learners that vary – the issues and materials, the institutional framework and the educational traditions also vary from country to country. This is the starting point for adaptation of this manual.

The units in this book offer tools that support political literacy, skills training and the development of attitudes. They do not refer to issues in any particular country at any particular time, but the reader will frequently find suggestions for the teacher or students to collect materials that link the units to the context in their countries. Editors and translators as well as teachers should be aware of this gap, which has been left deliberately. Just as each country develops its own tradition of democracy, rooted in its cultural tradition and social development, each country must also develop its equivalent version of EDC/HRE, by adding references to its educational and school system, the institutional framework of its political system, political issues and decision-making processes.

Which key concepts are included in this manual?

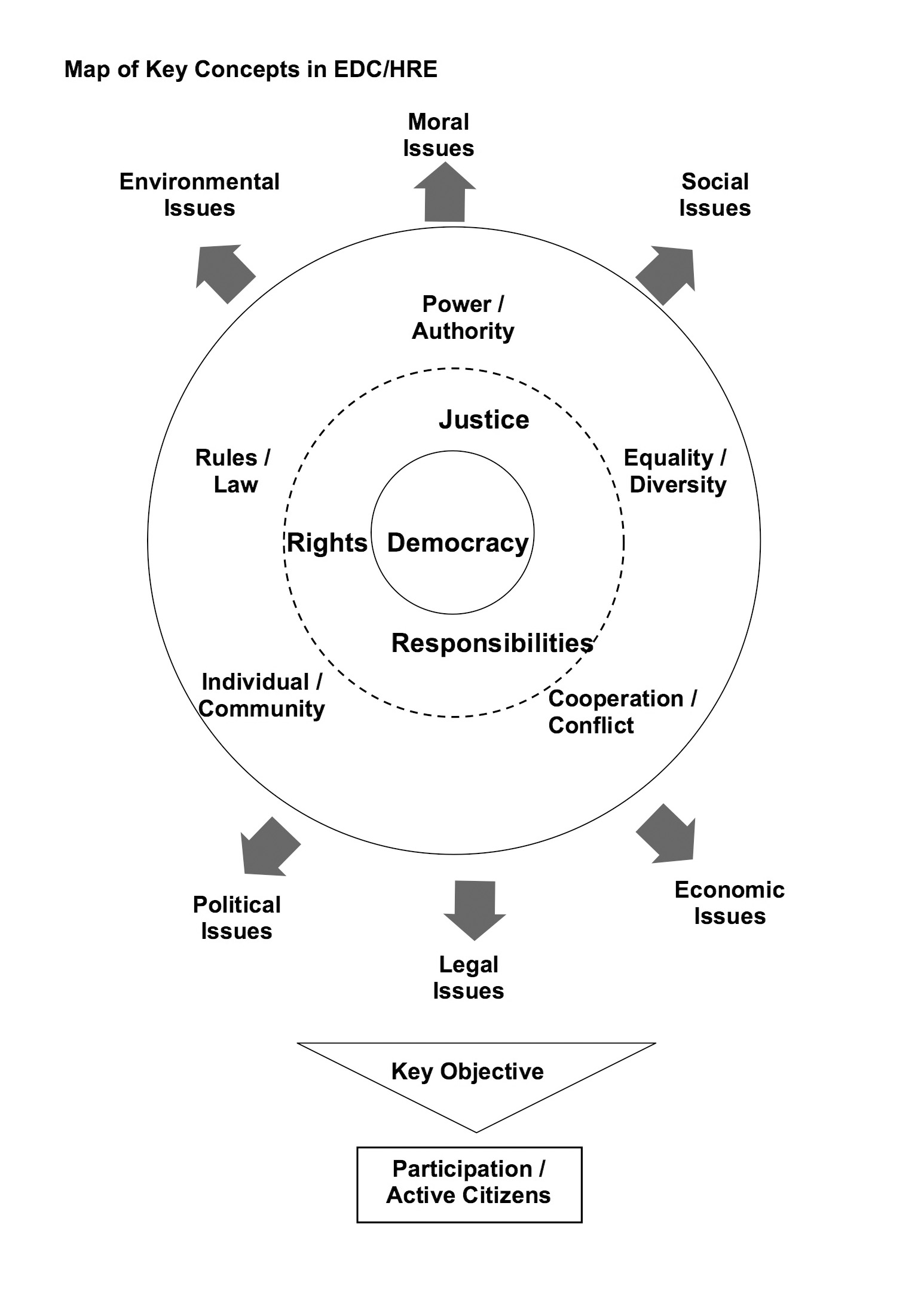

The concept map below, designed in concentric circles, shows which key concepts have been included by the units in this manual.

Democracy is in the centre of the map to indicate that this concept is present in every context of EDC/HRE. Participation in the democratic community by active citizens is the key objective of EDC/HRE, and this is reflected by the focal position of this concept.

In the next circle, three key elements of democracy are addressed: rights, responsibility and justice. They refer to three interdependent and important conditions that are necessary if democracies are to succeed.

Citizens must be granted, and make active use of, basic human rights that enable them to participate in decision-making processes – for example the right to vote, freedom of expression, freedom of the press, equality before the law, and the right to majority rule. Democracy is competitive – there is competition between interests, ideas and values and valuable goods are scarce. However, the opportunities to influence decision making, particularly in competitive market economies, are unequally distributed, and in society there is unequal distribution of welfare and opportunities. It is a political issue whether and to what extent the results of economic and social distribution need to be corrected (social justice). Citizens may and should use their rights to protect their interests, but no community can survive if its members are unwilling to care for each other or their common interests (responsibility). This brief sketch shows that the concepts do not stand alone, but are linked to one another by tensions that need to be balanced, and therefore understood.

The other concepts, arranged in the outer circle, are linked with these core concepts and with each other in many ways.

The arrows pointing outwards indicate that all these concepts may be used in dealing with issues of different kinds – moral, social, economic, legal, political or environmental.

Key concepts and learning dimensions in EDC/HRE

The key concepts are linked both to the subject matter of the units and the three learning dimensions in EDC/HRE that were already outlined in the introduction. The following table shows what the units contribute to teaching about, through and for democracy and human rights. The table also shows how and why the units have been grouped under four headings that refer to key aspects of EDC/HRE:

1. Individual and community;

2. Taking responsibility;

3. Participation;

4. Power and authority.

Arranged under these four headings, the units form a course. Part 1 begins with the individual and then focuses on society – social interaction, stereotyping, diversity and pluralism, pluralism and conflict. Part 2 raises the issue of who should take responsibility in the community. In Part 3, Unit 5 (Newspaper production) stands on its own, as this unit comes closest to taking action in the community – in this case, the school community. Finally, Part 4 looks at the law, legislation and politics, both on a general level and in the context of a school parliament.

| Unit No. | Title | Key concept in EDC/HRE | Teaching about – through – for democracy and human rights | ||

| “about” | “through” | “for” | |||

| Part 1: Individual and community | |||||

| 1 | Stereotypes and prejudices. What is identity? How do I perceive others, how do they see me? | Identity Individual and community |

Mutual perception Stereotypes Prejudice Individual and group identity | Switching perspectives | Recognising and questioning stereotypes and prejudices |

| 2 | Equality. Are you more equal than me? |

Equality Discrimination Social justice |

Discrimination in society Equality as a fundamental human right |

Appreciation of difference and similarity Switching to the perspective of victims of discrimination |

Challenging situations of discrimination Moral reasoning |

| 3 | Diversity and pluralism. How can people live together peacefully? |

Diversity Pluralism Democracy |

Pluralism and its limits Equal rights and education Protection of vulnerable persons or groups by human rights treaties |

Tolerance Focus on issues rather than people |

Democratic discussion Exploratory debate Negotiation |

| 4 | Conflict. What to do if we disagree? |

Conflict Peace |

Win-win situation Wants, needs, compromise |

Non-violence | Six-stage model of conflict resolution |

| Part 2: Taking responsibility | |||||

| 5 | Rights, liberties and responsibilities. What are our rights and how are they protected? |

Rights Liberties Responsibility |

Basic needs Wishes Human dignity Responsibilities and human rights protection |

Awareness of personal responsibility | Identifying and challenging human rights violations |

| 6 | Responsibility. What kind of responsibilities do people have? | Responsibility |

Legal, social, moral responsibilities Role of NGOs in civil society |

Moral reasoning Solving dilemmas (conflicts of responsibility) |

Taking personal responsibility |

| Part 3: Participation | |||||

| 7 | A class newspaper. Understanding media by producing media |

Democracy Public opinion |

Types of print mediaPurpose of news sections |

Freedom of information and expression Planning Joint decision making |

Taking personal responsibility for a project |

| Part 4: Power and authority | |||||

| 8 | Rules and law. What sort of rules does a society need? |

Rules and law Rule of law |

Purpose of law Civil law, criminal law Laws for young people Criteria for a good law |

Identifying fair laws | Respecting the law |

| 9 | Government and politics. How should society be governed? |

Power and authority Democracy Politics |

Forms of government (democracy, monarchy, dictatorship, theocracy, anarchy). Responsibilities of a government |

Freedom of thought and expression Critical thinking |

Debating |

Grouping the units under key aspects gives the teacher more flexibility in lesson planning. Questions raised by the students in one unit often anticipate the switch of perspective in a subsequent unit, which allows the teacher to respond better to the learners’ needs.

As described above, all units in this manual follow an inductive approach. The table shows categories linked to these key concepts within the units (learning about democracy and human rights). The second learning dimension of EDC/HRE, development of democratic attitudes and values, is directly addressed in Part 2, Taking responsibility. There is, however, a values dimension in every unit, as the column “Teaching through democracy and human rights” shows. The third learning dimension of EDC/HRE, learning how to participate in the community (learning for democracy and human rights), is also addressed in every unit, with Unit 5 focusing most strongly on this dimension.

The lesson plans include boxes on conceptual learning. Here, not only the key concepts are explained, but other concepts that are important in the context of the lesson are also introduced.

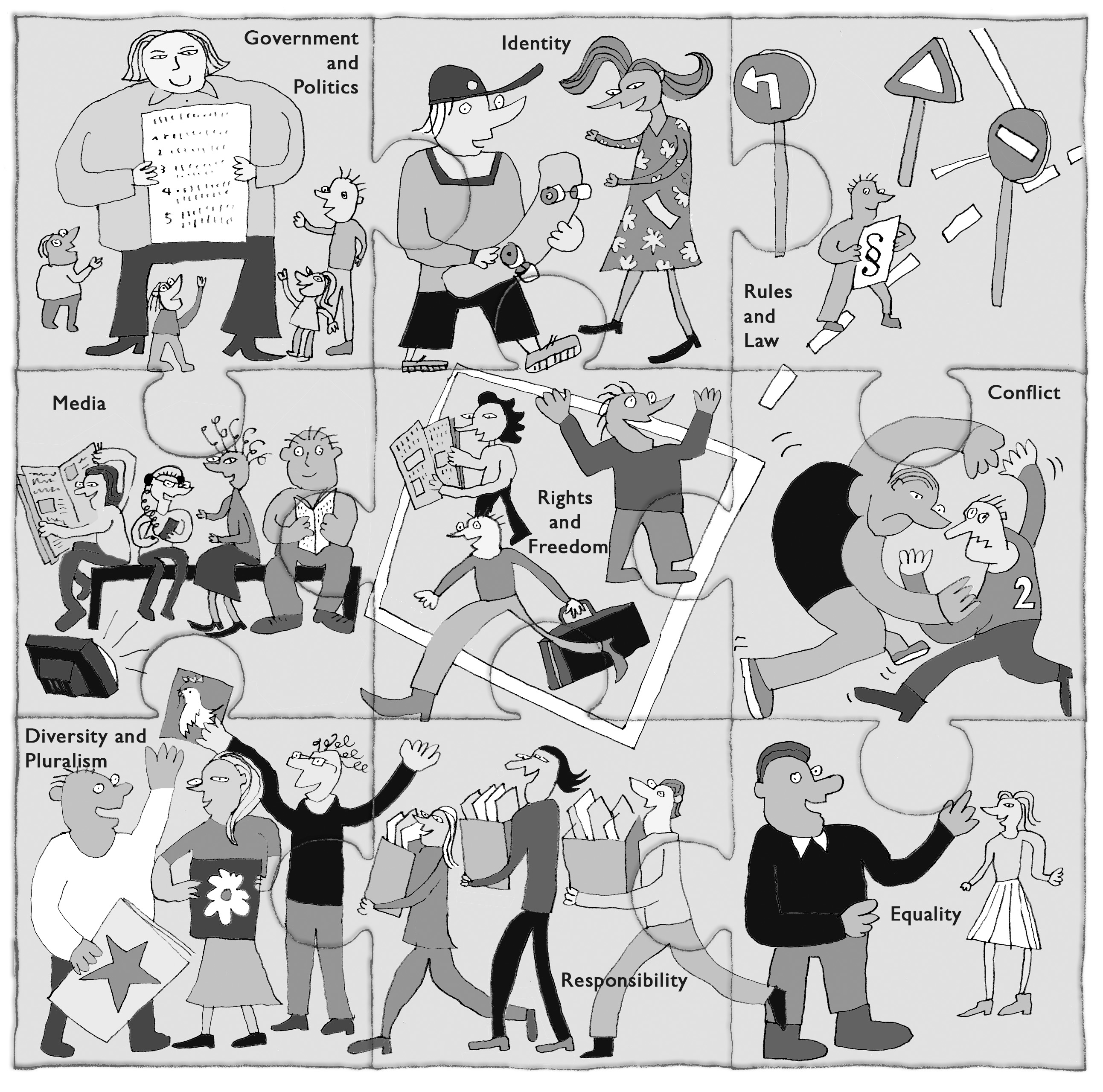

The concept puzzle – a model of constuctivist learning

The concept puzzle runs through the book like a leitmotif. It reappears on the title page of each unit, with the piece related to the key concept of that particular unit shown in the foreground. Here, the nine illustrations have been put together to form the complete puzzle. This image may be read in various ways.

First of all, the text in each picture makes clear which concept of EDC/HRE the artist, Peti Wiskemann, had in mind. Then, by connecting the nine pictures, the puzzle indicates that the nine concepts are linked in many ways and form one meaningful whole.

However, the puzzle gives us the impression that the set of key concepts in this book is complete in itself, and that no element may be omitted or added. Viewed from this angle, the puzzle might seem to convey a misleading message, suggesting that no didactic choice was made in the conceptual framework of this manual.

Of course, these nine concepts do not form a closed system of theory or understanding. Rather, they were chosen because we felt them to be particularly important or useful. Others would have been interesting too, for example money, power, or ideology. The manual provides a toolbox rather than a theory, and is open to adaptation and additions.

On the other hand, the attempt to understand is a search for meaning, and constructivism conceives the process of learning as an effort to create meaning. Learners link new information to what they already know and what they have already understood. The puzzle may thus be read as a symbol of how meaning is created by a learner. Students will try to link the key concepts of EDC/HRE to one another. In doing so, they will create their own puzzle in their minds, with different links and their own individual arrangement of the elements. Perhaps they will discover gaps or missing links and ask questions that go beyond the aim of the handful of key concepts in this book. Their results will differ, and the puzzle will reflect this by showing the concepts in a different order than the diagram and table above. Students may make mistakes when they create their own puzzles and so they should share their results in class. If necessary, a student or teacher should correct them (deconstruction).

When the teacher uses this manual and prepares lessons, he or she will have an idea in mind as to how these concepts are linked and how the students may, or should, understand them.

As the proverb says, a picture says more than a thousand words. Thus, this puzzle can tell the reader a lot about the key concepts in this book, about the implications of making didactic choices and about constructivist learning.

Images support the active reader (metareflection)

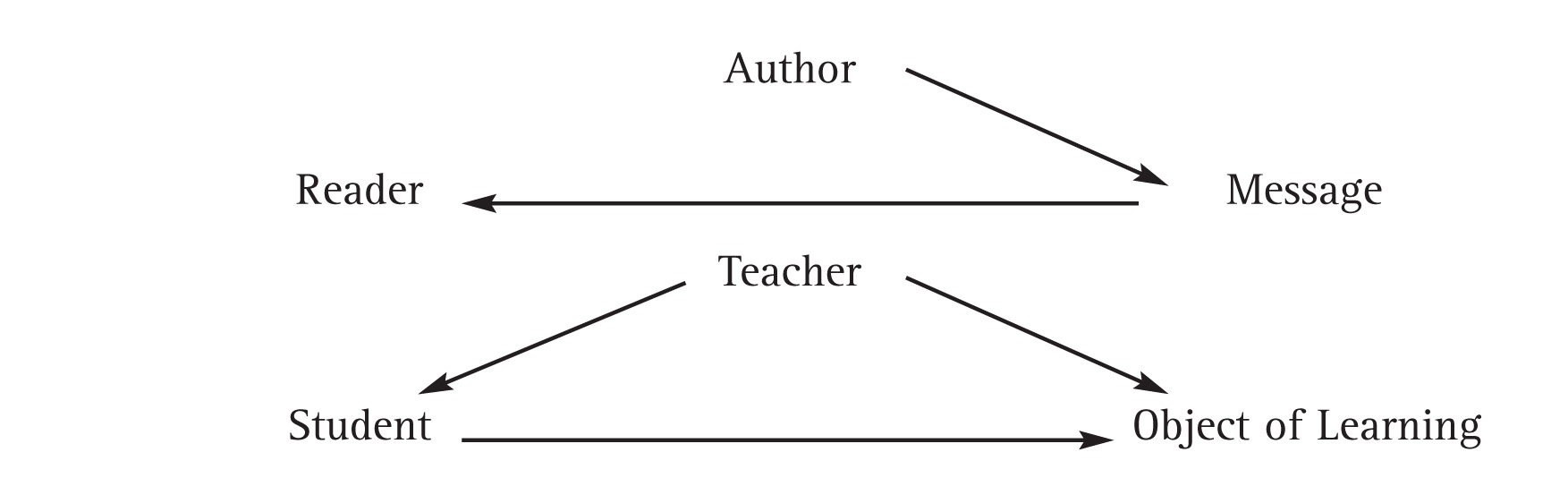

This chapter has dealt with an abstract idea – concepts. The author has a difficult task in making his message clear and the reader has a difficult task in understanding it. This shared experience of author and reader has a lot in common with the interaction between teachers and students. It is therefore worthwhile reflecting on the communication between author and reader in this chapter. In doing so, we are once more using an inductive approach, drawing on a concrete, shared experience in order to gain a general insight that may be applied in other fields, particularly teaching and learning.

Research has shown that many users of books look at pictures and diagrams first before studying the text. The strength of pictures lies in their aesthetic appeal to our imagination and in their concentration of information. Their weakness is that this information is transmitted non-verbally. The viewer may construct an idea in his or her mind that runs contrary to the author’s intention.

Author, reader and message form a triangular relationship. In this structure, one element is always absent from the relationship of the other two. This means that the author has no complete control over the message that the reader forms in his or her mind, just as no teacher can decide what a student finally remembers or forgets. However, if the reader is interested and willing to find out whether his or her understanding of the image is correct – whether it corresponds to the author’s intended message – then the author should provide a text that comments on or explains the image.

It is interesting to compare the structure of communication between author and reader with that of the teacher and students in the model of the didactic Mangle. There are structural analogies, and significant dijferences.

In both cases, there is a triangulär structure, which means that no one dement or player dominates the whole. Authors communicate with their readers through a medium such as this manual. It is usually a one-way communication. Author and reader rarely meet in person, and the author receives no regulär feedback. The author has no complete control over the message that emerges in the reader’s mind.

In class, the teacher has no complete control over the student’s processes of learning. However, the personal relationship between students and teacher provides permanent feedback, and the teacher’s personality is the most powerful medium in the process of teaching.

While looking at an image, the reader constructs a message in her or his mind and anticipates what to expect when reading the text that the author has provided. Perhaps the reader will find that his or her understanding of the image is confirmed, or perhaps he or she will experience deconstruction of some elements. Images help to create a dialogue between author and reader that takes place in the reader’s mind. The combination of image and text supports the active reader – and thinker.

Reading images is a key skill in the so-called information society and students should be trained in this skill. We therefore suggest that the teacher share this puzzle with students. Explaining the picture is a task that rests either with the teacher or with the students. The teacher could use it to introduce the students to the curriculum that this manual offers, or perhaps as a summary at the end of the school year. The students could cut up the puzzle into nine pieces and reconstruct it according to the actual curriculum that has emerged in their minds. By sharing their personal combinations and links of the puzzle pieces and the concepts they stand for, the students will become aware of their own ways of learning and understanding. Reflecting on this experience at the level of conceptual learning, they may come to understand that freedom of thought and expression are not only conditions of democratic decision making, but also of reading and learning.