Lesson 3: Whose problem is it?

Living Democracy » Textbooks » Living in democracy » Part 2: Taking responsibility » UNIT 6: Responsibility » Lesson 3: Whose problem is it?How are social responsibilities shared?

| Learning objectives | To consider the shared nature of responsibility for social problems. |

| Student tasks | Students discuss responsibility for certain social problems. Students complete a thinking frame. Students produce written responses to the issues raised. |

| Resources | Copies of the “letter”. Blackboard. Paper for individual student writing. |

| Methods | Structured critical analysis. Small group analysis and discussion. Consensus reaching and negotiation. Personal writing. |

Conceptual learningSocial problem: A problem experienced by all or many members of a community the responsibility for which is shared by different parts of the community or by the community as a whole. Responsibility for a social problem is not necessarily shared equally between the parties involved. Degree of responsibility: The extent to which someone may be responsible for a social problem. |

The lesson

The teacher introduces the imaginary letter to the local newspaper. This contains complaints about two social problems worrying the residents of a town.

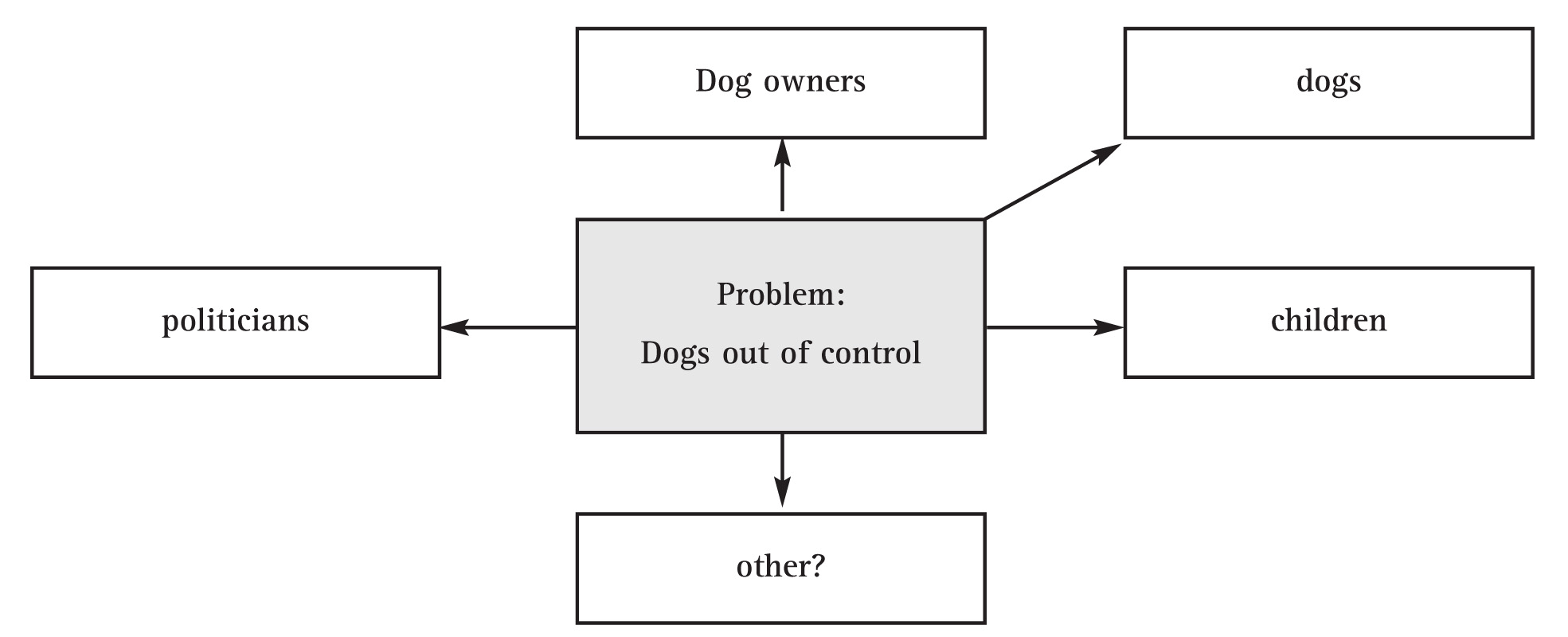

The teacher asks the students as a class to: a) identify the issues and b) make a list (for both issues) of those people who might have responsibility. The teacher can assist this process by drawing a thinking frame on the blackboard as shown below.

Who is involved in this problem in any way?

Group work

Step 1

Divide the class into groups of three or four. Give each person in the group a number of points equal to the number of parties involved.

Step 2

Each member of the group first divides up the points between the parties according to how they think the responsibility for the problem should be shared. For example, the children and dogs might get no points, but dog owners and politicians could share the points between them or one of these might get more points than the other.

Step 3

When each member of the group has made his or her own decision, they take it in turns to share their ideas with each other, giving their reasons. Students can change their minds at this stage. Finally, each group totals the points awarded to each party. This represents how the group as a whole thinks the responsibility for this problem should be shared.

The teacher discusses with the whole class the conclusions reached by the different groups. The teacher explores the different views put forward, eliciting from the students their underlying reasons for these judgments.

If time allows, repeat the exercise with the problem of litter and rubbish. Or substitute a problem more relevant to the locality of the school or more challenging to the ability of the group.

Note

The problems given in these examples are suitable for students who are not yet very experienced in discussing political problems. This is because they are concrete, visible and relatively easy to understand (although they are still quite hard to solve). Older or more able classes should be asked to discuss more sophisticated problems, such as unemployment or racism, using the same kind of thinking frame.

Step 4: Discussion arising from the exercise

In the final plenary session, the teacher asks the students to consider whether people generally take enough responsibility for their actions. If not, consider how they might be persuaded to do this. Will education help in any way? Or is it necessary to create new laws or introduce stiffer penalties? If local or national government should accept responsibility for certain problems, ask students about the likely cost and how this should be paid for. The teacher could also ask the class to consider the role of young people in addressing social problems of this kind. Should they be excused from responsibility because of their age? Is it right for young people to leave problems in the community to adults? Such issues could form the basis of a personal written task.

The teacher explains the need for local and national politicians to be aware of problems as they develop. Politics is often about tackling shared problems as a community. This does not mean that governments can solve every problem, and many problems would not even arise if people took more responsibility for the consequences of their actions in the first place.