Interactive constructivist learning in EDC/HRE

Living Democracy » Textbooks » Taking part in democracy » Interactive constructivist learning in EDC/HRE1. Key questions on didactics in EDC/HRE

In EDC/HRE, as in teaching generally, it is important for the teacher to reflect on the objectives of and to clarify the reasons for the choices that must inevitably be made and the priorities that must be set.

- What must students learn in EDC/HRE?Students should learn how to participate as citizens in their democratic community. They need to develop:

- competences of political analysis and judgment when dealing with political problems and issues;

- competences of participation in political decision-making processes; plus

- a repertoire of methodical skills.

- Why and for what should students acquire these competences?Democracy depends on citizens who are willing and able to take part in decision making, and to take office in its institutions. Students need these competences and skills to be able to exercise their human and civil rights and to perform their roles as active citizens (“learning for” democracy and human rights).

- This raises a further question. If this is what young citizens should learn – in terms of learning output – what must EDC/HRE teachers do to ensure this?EDC/HRE teachers must deliver inputs to support their students’:

- knowledge and conceptual learning – “learning about” democracy and human rights;

- skills training; and

- teachers must also provide role models and learning environments for attitudes and values that are supportive of a democratic culture (tolerance, mutual respect, appreciation of human rights) – “learning through” democracy and human rights.

- The three questions above have already been addressed in the introduction to this manual. However, one important question remains: how do students learn in EDC/HRE?As EDC/HRE teachers, we must have some understanding of how our students’ processes of learning take place and how we can support them. To answer the question on how our students learn, we have adopted a conceptual framework of interactive constructivist learning. With this approach, we link “learning through” democracy and human rights in EDC/HRE classes to political decision-making processes in democracy. Decision-making processes in democracies are essentially collective processes of learning. This is the reason why John Dewey conceived of school “as a miniature community, as an embryonic society”.2 In this chapter we put forward our understanding of interactive constructivist learning. We believe it helps EDC/HRE teachers to better understand:

- their students’ processes of learning in EDC/HRE;

- their role to support their students in learning;

- that democratic decision making is a process of collective learning.

Teaching and learning in EDC/HRE and politics in democracy can both be perceived from a constructivist perspective. This is possible and useful due to the structural analogies between constructivist learning and democratic decision making. Both EDC/HRE classes and democratic communities are, or at least should be, learning communities governed by human rights. Therefore interactive constructivism reinforces the basic approach of EDC/HRE – teaching through, for and about democracy and human rights: it is good teaching, it serves human rights, and also supports the learning needs of students and citizens.

Theory is best introduced by a concrete example. The following section therefore illustrates the potential of interactive constructivist learning in children’s rights education.

2. An example of interactive constructivist learning – young pupils imagine their ideal world

Volume V of this EDC/HRE series, Exploring children’s rights, includes a four-lesson unit for third grade pupils entitled, “We are wizards!”.3 It encourages the pupils to express their wishes and ideas as to how the world should be, and in the follow-up discussion, they explore the moral and political implications of their wishes for the future world.

The first lesson begins in the following way:

“The teacher draws two persons on the board: an ordinary woman or man and a wizard.

| Hunger |  |

| Poverty | |

| Boredom | |

| Birthday | |

| … |

In pairs, the children should also draw the two figures and try to answer the following questions together:

- What does the ordinary person do in certain situations?

- What does the wizard do in the same situations?

After a few minutes, the teacher assembles the pupils in a semicircle in front of the blackboard to give every child a good view (in big classes, a double semicircle may be necessary). He or she collects all the pupils’ answers in a list on the board – without commenting or judging. We suggest the following table to integrate the pupils’ ideas.

We look at the solutions and let the children give their comments. Of course, now questions will arise! The teacher wants to know:

- Can you see any solutions or ideas that have been made by a good or a bad wizard?

- When did you last wish you were a wizard, and what did you want to change then?

- What is your biggest wish right now?The teacher encourages the pupils to come forward with their ideas and gives them all positive support. (…)”

This example demonstrates some important aspects of how students and teachers interact in constructivist learning settings:

| The teacher … | The pupils … |

… sets an open task that:

… collects the pupils’ ideas on the board; … adds structure (keywords and concepts); … improvises in doing so, reacting to the pupils’ inputs; … asks questions to help the students explore the reasons for and implications of their ideas; … encourages the pupils and gives positive feedback. |

… develop and share their ideas;

… express and share their ideas;

… think about their wishes and their experience of limits and restrictions on those wishes in real life; … discover the difference between “good” and “bad” wizardry. |

A basic principle of constructivist learning is that the pupil’s outlook matters. In this case:

- How do pupils perceive the world they live in?

- How do they judge what is happening around them?

- What would they change if they could?

- What is their most serious concern – the one at the top of their personal agenda?

- What views do they share in class – in what respect do they differ?

- It is also apparent that the pupils judge what is happening in their world, and their judgment strongly influences the way in which they will take action and participate.4

In constructivist learning, learners are allowed to act in the role of experts. Teaching arrangements focus on what students already know, rather than what they do not know. In the role of wizards, every child can contribute an idea, and there is no “right or wrong” standard. Rather, the reasons why a child expresses a certain vision is important – what experiences are involved? What concerns the child? What are the boy’s or girl’s wants and needs? Constructivist learning takes the individual learner’s perspective and process of learning and thinking into account.

Constructivist learning is an exercise of human and children’s rights – freedom of thought, opinion, and expression; equality of opportunity; principles of mutual recognition and non-discrimination; and the right to education.

In constructivist learning settings, the teacher’s task is to support the pupils in many ways – he/she provides a task-based and/or problem-based framework, respects the pupils’ rights of liberty and equality, gives guidance, encouragement and instruction (concepts). The teacher does not know the answers the pupils will give, and is willing and prepared to work with their inputs (improvisation). The pupils must have the opportunity to share and compare their ideas, and often their topic or task requires them to reach a joint understanding or to make a decision. The teacher acts as a facilitator; he/she can anticipate, but cannot predetermine the outcomes of the students’ processes of learning.

Constructivist learning supports competence development rather than the intake of a set of facts. From a constructivist point of view, every knowledge-based curriculum can be challenged, and it doubtful whether anyone can “learn” by memorising isolated facts without understanding and appre-ciating them.

The following section explores this issue in somewhat more detail. It looks at some aspects of learn-ing theory in interactive constructivism and links them to a constructivist concept of democratic decision making.

3. Every person learns differently —“We create the world in our minds”

When we read a story in a book, we create something like a movie in our minds. We add details and scenes that the author hints at or leaves out, and we may even imagine the faces of the characters. Some novels appeal so strongly to our imagination that we are disappointed if ever we watch a “real” movie based on the story. Our imagination had produced a far better one, and it is unique, as every reader’s mind produces a different “movie”.

This is an example of our capability to “create the world in our minds”. The world that we live in is the world as we perceive it – it consists of the images, experiences, concepts and judgments that we have created. As learners, people want to make sense of what they hear or read – they want to understand it. A brain researcher characterised the human brain as a “machine seeking for meaning”. Things that do not make sense must be sorted out somehow. If information is missing, we must either find it, or fill in the gap by guessing. Stereotypes help to simplify complicated matters.5

With experience, teachers find out that when they give a lecture, each student receives and stores a slightly different message. Some students will still remember the information when they are adults because it appealed to them so strongly, others may have forgotten it by the next morning because it was not meaningful for them. From a constructivist perspective, it is important what happens in the students’ minds.

Constructivism conceives learning as a highly individualised process:

- Learners construct or create structures of meaning. New information is linked to what a learner already knows or has understood.

- Learners come to an EDC/HRE class with their individual biographies and experiences.

- Gender, class, age, ethnic background or religious belief give each learner a unique outlook.

- We possess different forms of intelligence that go far beyond the conventional understanding of being good at maths or languages.6

- There is no absolute standard for personal or political relevance. Something becomes a problem because a person defines it to be so, and the learner’s mind selects the information that will be remembered or forgotten.

4. Constructivist learning and social interaction

So far we have looked at the individual learner’s perspective. Learners seek for meaning, but learners also make mistakes. How are they to be corrected? From a constructivist perspective, it is the learner who must deconstruct, or dismantle, what is wrong and rebuild it. But how does an individual learner become aware of the mistakes he or she has made? There two ways for a learner to overcome short-comings and mistakes.

First, we discover our mistakes ourselves. We find out that our solution to a problem does not work, or a line of argument does not make sense.

Second, we depend on others to tell us, and often to help us.

Constructivist learning is therefore not only a highly individualised process. It also has a second, equally important, dimension of collective learning. Learners must share their ideas through interac-tion and communication with each other and with their teachers. For this reason, we have termed our concept interactive constructivist learning.

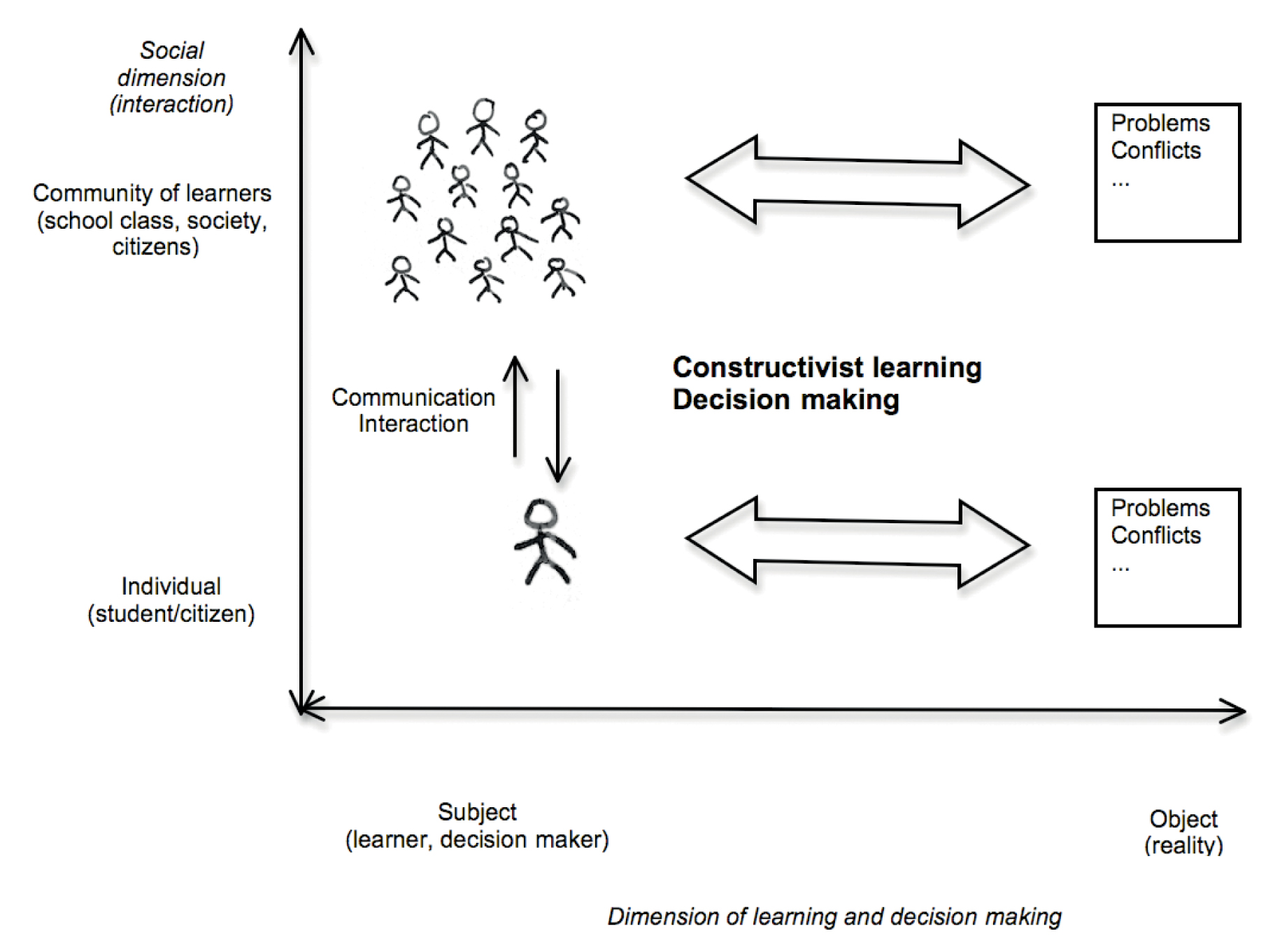

The following diagram illustrates the individual and social level of constructivist learning; this is the social dimension of constructivist learning.

It also shows that learners always refer to the world outside their minds. When they put their ideas and plans to the test, it is the world of objects that is their point of reference. This is the subject–object dimension of constructivist learning.

Both students in class, and citizens in a democratic state interact as communities of learners. We already referred to John Dewey, who conceived of school “as a miniature community, as an embryonic society”.7Therefore the interaction that students experience in school with each other and with their teachers is part of real life, rather than an artificial arrangement to prepare them for real life later on.

Both in politics and in school, there are always members present with higher levels of experience, knowledge, understanding, and also power – teachers, political leaders, managers, scientists and so on. However, in modern societies none of these players exercises absolute power. Democracy and the rule of law (should) set limits to any player’s powers, and these limits are reflected by the division of labour, confining every player to being a specialist in a certain field.

However, there is a serious threat to the democratic pledge that everyone has the equal opportunity to take part in democracy. The more complex our societies and the problems to be solved become, the more the individual citizen depends on his or her competences to take part in democracy. More than ever before, education has become the key to participating in the adult community of learners.

5. What is the teacher’s role in processes of constructivist learning?

Learners search for meaning, and each learner does so in a highly individual manner. A learner links new information – a piece of information, a lecture, an interesting idea in a book, etc. – to the exist-ing structures of knowledge and experience in the learner’s mind. Constructivism means we create our systems and structures of knowledge, understanding and experience.

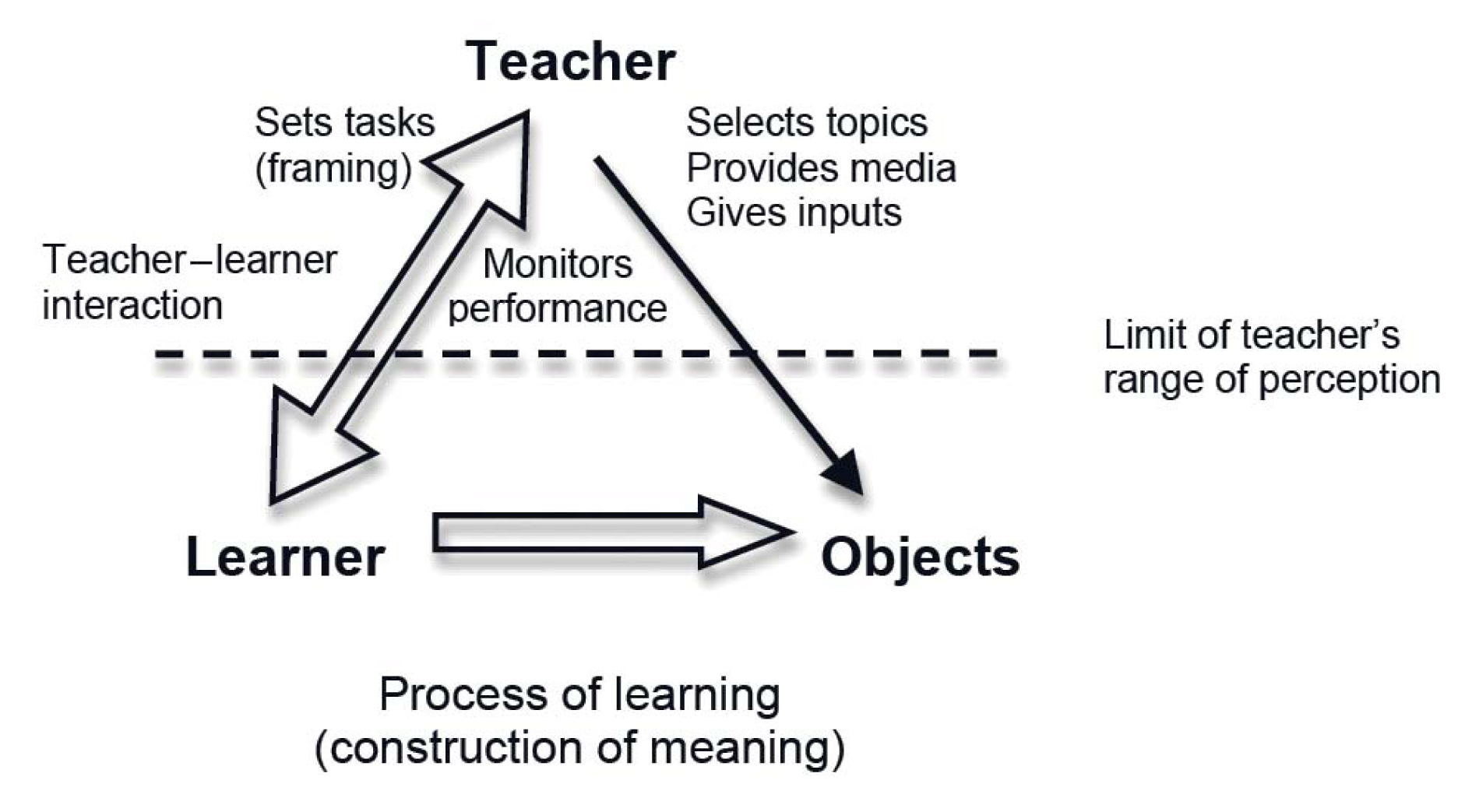

From a constructivist point of view, the well-known didactic triangle takes on a new meaning:

In triangular relationships, one party is sometimes excluded. In processes of constructivist learning, it is the teacher. It is the learner who creates his or her understanding of the objects of learning. The construction of meaning takes place in the learner’s mind, beyond the teacher’s range of perception. What the teacher sees is the outcome – what students produce, and how they behave. The teacher sees the performance, not the competence. And it is the students, not the teacher, who will ultimately decide what they find interesting and worth learning, and what they will remember for life, or forget.

Constructivist learning can be further differentiated into three sub-categories, and the teacher plays an important part in supporting them.

- Learners construct meaning – they discover and create something new. Teachers can support their students by:

- creating learning opportunities;

- designing challenging tasks;

- providing instruction through media and inputs (lectures) that represent the objects of learning;

- encouragement and support for the learner’s self-esteem;

- …

- Learners reconstruct what they have learnt – they apply it and put it to the test. To a large extent, we all create such applications ourselves, but in school, the teacher provides them by:

- giving opportunities for sharing, presentation and discussion;

- by formal testing and assessment;

- by offering or requiring portfolio work;

- by designing challenging tasks, for example in projects;

- …

- Learners deconstruct, or criticise, their own results or each other’s. As already outlined above, without this element of critical review and testing any learning effort would become irrelevant for society, and for the individual learner himself.

6. What is the teacher’s role in EDC/HRE?

A key element of teaching and learning is how students communicate and interact with each other and with the teacher. The teacher’s professional competence enables him/her to reflect on the effect of a certain activity, and to employ such patterns of behaviour like tools. The teacher performs in different roles, and these are more differentiated than in traditional content-biased frontal instruc-tion (“chalk and talk”). Instruction is one role that a teacher must perform, but in this case less often. Rather, constructivist learning requires the teacher “to teach with his mouth shut”, giving more time, and more of the floor, to the students.

The following sections outline four key roles that a teacher typically performs in constructivist learning settings:

- The teacher as lecturer and instructor.

- The teacher as critic and corrector.

- The teacher as creator and provider of application tasks.

- The teacher as chair in plenary sessions.

Rather than giving abstract instructions on how to perform these roles, the examples refer to the lesson descriptions in the manual where the reader will find detailed descriptions of the context in EDC/HRE classes.

6.1 The teacher as lecturer and instructor – to support and enrich construction

A basic rule for a lecturer is the “60:40” principle; 40 per cent, preferably more, of what you are talking about should be familiar to the students. Without this high degree of redundant information no constructivist learning is possible.

In this manual, the key concepts form the didactic backbone, as it were, of the EDC/HRE curriculum. These concepts must be introduced to the students, and this means the teacher must instruct the students by giving a lecture or a reading task, or both. As constructivist learners, they must have already created a context of meaning into which the teacher’s instruction will fit. Typically this open, unfinished structure of meaning consists of questions or experiences in need of explanation. The following table shows where the teacher’s role as lecturer and instructor is addressed in the lesson descriptions of this manual.

| Unit No. / Key concept | Examples and references to the materials |

| Unit 2 Responsibility | Lesson 4: The teacher selects a topic that the students have focused on in their discussion and gives a conceptual framework for reflection. Materials for teachers 2.3 provides the lecture modules to support the teacher in his/her preparation. |

| Unit 3 Diversity and pluralism | Lesson 2: The teacher introduces the concept of the common good (see materials for teachers 3B). |

| Unit 4 Conflict | Lesson 3: The students have reported on their experience of conflict. The teacher helps them to understand the problem that gave rise to this conflict by introducing the model of sustainability goals (see student handout 4.2). |

| Unit 4 Conflict Unit 5 Rules and law |

The students have taken part in one or two decision-making games. The teacher helps the students to reflect on their experience in the debriefmg Session by introducing the concept of modernisation (see student handout 5.5). |

| Unit 6 Government and politics | Lesson 2: The teacher introduces the policy cycle model student handouts 6.1 and 6.2). In a brainstorming session during the previous lesson the students have discussed the issue of political agenda setting and are now ready to receive this input. |

| Unit 9 The media | Lesson 1: The students have expressed their preference for a certain type of newspaper. The teacher links their statements to the concept of gatekeeping. Not only the media act as gatekeepers, the users do so too. |

| Lesson 4: The students reflect on their role in constructing media messages. The teacher addresses two key points in media news production: all media messages are carefully constructed, and media editors and news producers act as gatekeepers and agenda setters (see materials for teachers 9A). |

6.2 The teacher as critic and corrector – to support deconstruction

As far as the teacher is concerned, no examples of her or his role as critic and corrector are included in the lesson descriptions in the manual – for the obvious reason that the occasion may arise at any time and cannot be anticipated. The teacher must realise what needs to be set right. Some general guidelines can be discussed, however.

Is the error relevant? In other words, is it necessary to correct the mistake at all?

Preference for student feedback: will the students have the opportunity, for example during a presentation or discussion, to discover the mistake later and correct it then?

However, in certain circumstances the student must correct – deconstruct – his/her construction of meaning and begin again. Example: the whole class will rely on the student’s presentation.

Principle of mutual respect: we may criticise each other’s mistakes – but we respect the person. This is important in order to support the students’ self-esteem, and to encourage them.

Unit 8 stages a debate among students. Here, the students put each other’s arguments to the test, and deconstruct them if they find any fault.

6.3 The teacher as creator and provider of application tasks – to support

reconstruction

Interactive constructivist processes of learning depend on adequate learning opportunities – including suitable objects, materials, time, rules, task instructions, monitoring, and individual support. In EDC/ HRE the teacher has the task of providing such opportunities of task and problem-based learning for the students. The following table shows which examples are included in the lesson descriptions of this manual.

| Unit No. / Key concept | Examples and references to the materials |

| Unit 1 Identity | Lesson 4: The students engage in a job-shadowing project to find out which job fits the criteria that they have defined in reflecting on their personal strengths and interests. |

| Unit 3 Diversity and pluralism | Lesson 3: The students have been introduced to the concept of the common good by the teacher. Now they engage in a decision-making game to negotiate compromises in terms of the common good. |

| Unit 4 Conflict | Research task: The students are introduced to a model of sustainability goals by studying the problem of overfishing. They carry out case studies to explore further sustainability issues, such as CO2 emissions or nuclear waste disposal. |

| Unit 4 Conflict Unit 5 Rules and law |

The teacher acts as game or process manager. He/she sets the time frame, and ensures that the rules of the game are observed, but does not deliver the solution to the problem that the students are dealing with. |

| Unit 5 Rules and law | Lesson 4: The teacher gives the students a questionnaire (student handout 5.6) to help them reflect on their process of learning. |

| Unit 6 Government and politics | Lesson 3: The teacher sets the students the task of applying the policy cycle model (student handouts 6.1 and 6.2) to a concrete example. |

| Lesson 4: The teacher selects one of three key statements that fit the context of the students’ feedback (see materials for teachers 6.2). In each key statement, a concept is introduced that helps the students to reflect on their work. But they should work with it thoroughly so the teacher should decide which concept to select. |

6.4 The teacher as chair in plenary sessions – to support all forms of constructivist learning

Teaching and learning through democracy and human rights perhaps becomes most apparent in plenary sessions when the students share ideas or hold discussions. Here they exercise their freedom of thought, opinion, and expression. Without thorough training in making use of these basic democratic rights, they will be unable to take part in democratic decision making.

In the lesson descriptions, we generally suggest that the teacher chair these sessions. It is a chal-lenging task, as the students confront the teacher with inputs and ideas that he/she must then work with. To a considerable extent, the teacher can anticipate the conceptual framework that will serve as a tool to give structure and meaning to the students’ inputs, but the teacher must also improvise.

The manual includes many descriptions of how to perform the role of chair. In broad terms, the teacher chairs two types of plenary session. First, he/she can start a lesson or unit off so as to allow the students to get involved quickly. Second, the teacher can chair a plenary session that begins with student inputs – homework results, a discussion, or feedback. The following tables show the examples included for both types of plenary sessions.

a. The teacher gives the first input to a plenary session

| Unit No. / Key concept | Examples and references to the materials |

| Unit 1 Identity | Lesson 1: Every day, throughout our lives, we make choices and decisions – what examples come to the students’ minds? |

| Lesson 3: Why do you attend school at upper secondary level? | |

| Unit 2 Responsibility | Lesson 1: What would you do if you faced this dilemma? |

| Unit 3 Diversity and pluralism | Lesson 1: The teacher supports the students in a brainstorming session. He/she guides the students to link and group ideas under new headings. |

| Unit 4 Conflict | Research task: The students are introduced to a model of sustainability goals by studying the problem of overfishing. They carry out case studies to explore further sustainability issues, e.g. CO2 emissions or nuclear waste disposal. |

| Unit 4 Conflict Unit 5 Rules and law | The teacher acts as game or process manager. He/she sets the time frame, ensures that the rules of the game are observed, but does not deliver the solution to the problem that the students are dealing with. |

| Unit 5 Rules and law | Lesson 4: The teacher gives the students a questionnaire (student handout 5.6) to help them reflect on their process of learning. |

| Unit 6 Government and politics | Lesson 1: The teacher supports the students in a brainstorming session (“Wall of silence”). He/she guides the students to link and group their ideas and opinions and to give them structure by grouping them and adding categories. |

| Unit 8 Liberty | Lesson 1: The teacher announces, “Every child should spend an additional year at school.” The students express their point of view on the issue – they agree or disagree. It is a political decision, so there is no alternative to “Yes” or “No”. |

b. The students give the first input to a plenary session

| Unit No. / Key concept | Examples and references to the materials |

| Unit 1 Identity | Lesson 1: The students give reasons for their choice of a quotation. The teacher shows the students how to record their ideas in a mind map. |

| Lesson 3: The students present their thoughts on how they will shape their future. The teacher cannot anticipate what the students will say, but a conceptual framework will allow him/her to work with the students’ inputs. | |

| Unit 4 Conflict | Lesson 3: The teacher chairs a debriefing session after a decision-making game. He/she listens to the students’ feedback, identifies the key statements and takes them down on the blackboard or flipchart. |

| Lesson 4: The students begin the lesson with their inputs that they have prepared at home. They set the agenda and create the conceptual framework for the whole lesson. The lesson description helps the teacher to anticipate the main points that the students will address and how to react to them. | |

| Unit 7 Equality | Lesson 1: The teacher reads a case story and asks the students just one question, “What is the problem?” The students think in silence and write down their answers. Many students then come forward with their ideas. The teacher encourages them to explain their reasoning. Then he/she links their ideas to a conceptual framework that can be anticipated. Unit 7, lesson 4 gives another example of this method. |

| Unit 8 Liberty | Lesson 1: The students have run through an exchange of arguments on an issue. The teacher asks, “What makes a good issue for a debate?” He/she sums up the students’ ideas, which can be expected to correspond to the criteria in student handout 8.1. |

7. Democracies as communities of learners – a constructivist approach to the key concepts in EDC/HRE

The concept of interactive constructivist learning not only conceives of an EDC/HRE class, and a school as a whole, as a community of learners governed by human rights, but also as citizens engaged in decision-making processes.

“Learning for” democracy and human rights therefore means that the students prepare for their roles as lifelong learners, both as individuals and as a community. There are two lines of argument to enforce this point.

The first is normative, referring to human rights. Citizens should have the opportunity to take part in democracy, and to express their views and interests when discussing any issue on the agenda. This implies that every decision-making process is open-ended; otherwise it would be a farce.

The second line of argument is analytical, referring to the complexity of our modern societies, their mutual global interdependence, and the daunting challenges of such issues as climate change, declin-ing biodiversity, the security risks arising through failing states, or the increasing gap between rich and poor – to mention but a few. No one has a clear idea of how to solve the problems awaiting us – either in our individual lives, or at the global level. We are learners, beset with the task of finding viable solutions.

The key concepts in EDC/HRE in this manual are therefore defined from an interactive constructivist perspective. The following chart sums up the basic conceptual approach to each of the nine units.

| Unit No. / Key concept | EDC/HRE: constructivist concept of … |

| Unit 1 Identity | … identity: we shape our identity through our key choices. |

| Unit 2 Responsibility | … responsibility: we create our common set of values. |

| Unit 3 Diversity and pluralism | … interests and the common good: we negotiate for what we consider to be the common good. |

| Unit 4 Conflict | … conflict: problems and conflicts are what we consider as such. |

| Unit 5 Rules and law | … rules and laws: they are tools that serve to solve problems and deliver the framework for peaceful conflict resolution. |

| Unit 6 Government and politics | … political decision-making processes: their purpose is to find solutions for urgent problems. |

| Unit 7 Equality | … inclusion and social cohesion. |

| Unit 8 Liberty | … the way we exercise our human rights of liberty, e.g. freedom of thought and expression. |

| Unit 9 The media | … our perception of the world through the media: producers and users of media as gatekeepers and agenda setters. |

2. John Dewey, The School and Society, New York, 2007, p. 32.

3. Rolf Gollob / Peter Krapf, EDC/HRE, Volume V: Exploring children’s rights, Council of Europe Publishing, Strasbourg, 2007, “We are wizards!”, pp.22-26; c.f. EDC/HRE Volume VI, Teaching democracy, Council of Europe Publishing, Strasbourg, 2008, Exercise 6.3, “If I were a magician”, p.59.

4. EDC/HRE can, and therefore should, be taught to very young children. EDC/HRE Volume V begins with a unit for children at kindergarten level who have not yet learnt to read and write. See Unit 1, “I have a name – we have a school”, pp. 13-16.

5. See Rolf Gollob/Peter Krapf (eds), EDC/HRE Volume III: Living in democracy, Council of Europe Publishing, Strasbourg, 2008, Unit 1, “Stereotypes and prejudices. What is identity? How do I see others, how do they see me?” pp. 19-38.

6. See Howard Gardner’s work on multiple intelligences.

7. John Dewey, The School and Society, New York, 2007, p. 32.