Lesson 3: What is the common good?

Living Democracy » Textbooks » Taking part in democracy » Part 1: Taking part in the community » UNIT 3: DIVERSITY AND PLURALISM » Lesson 3: What is the common good?Consent through dissent

| This matrix sums up the information a teacher needs to plan and deliver the lesson. Competence training refers directly to EDC/HRE. The learning objective indicates what students know and understand. The student task(s), together with the method, form the core element of the learning process. The materials checklist supports lesson preparation. The time budget gives a rough guideline for the teacher’s time management. |

|

| Competence training | Participation: negotiation skills. Analysis: analysing goals for shared intent. |

| Learning objective | Politics has two dimensions: the solution of problems and the struggle for power. Compromise is the price to pay for support and an agreement. |

| Student tasks | The students negotiate a decision. |

| Materials and Resources | A4 paper strips and markers. Demonstration strips for the “diamond analysis”. |

| Method | Decision-making game; individual, group and plenary sessions. |

| Time budget | Stage 1: The students define their proposals. (10 min) |

| Stage 2: The students negotiate at a round table. (30 min) | |

Information boxThe unit models the process of negotiating goals defined by a shared understanding of the com-mon good. In this lesson, the students’ task is to strive for this goal. They may succeed, or they may not. Their effort and experience is as important as the result. The teacher continues performing in the role of a facilitator. For example, he/she presents models for negotiation but does not comment on the contents. During the first phase, special attention should be given to those students who experience exclu-sion because they have not joined a party. |

Lesson description

Starter: the teacher gives details of the schedule

The teacher refers to the schedule ( student handout 3.1) and reminds the students of their task. In this lesson, they will negotiate a political agenda. What goals do they propose?

Stage 1: The students define their goals

The students decide what goals to propose. Parties and individuals alike can make a proposal. This seems to give individual “non-aligned” students an advantage; on the other hand, a parry proposal has a better chance of being voted to the top of the agenda.

The group speakers or individual students prepare a brief promotion statement.

The students note their goal on a paper strip using a marker.

Stage 2: The students negotiate at a “round table”

The teacher insists on beginning punctually The students are seated in a circle of chairs; this does not quite fit the “round table” metaphor, but supports communication best. Parties who have formed a coalition sit next to each other.

Step 2.1: The students make their proposals

The teacher opens the round table talks and gives each parry speaker, and also individual students, the chance to take the floor. The teacher requests them to report on any agreements they have made, and to make a proposal for a joint decision. They lay down their paper strip on the floor.

Step 2.2: The students analyse their goals and explore opportunities of compromising and Integration

After everyone has spoken, the teacher facilitates possible links and compromises between the students’ proposals.

Do some of the proposals fit together well? Can these cards be clustered?

Which proposals exclude each other? Here the students should look at the proposals carefully. Do the goals exclude each other? Or do the goals share the same intent, but demand a big input of effort, resources or money?

Step 2.3: The teacher suggests a model for negotiation

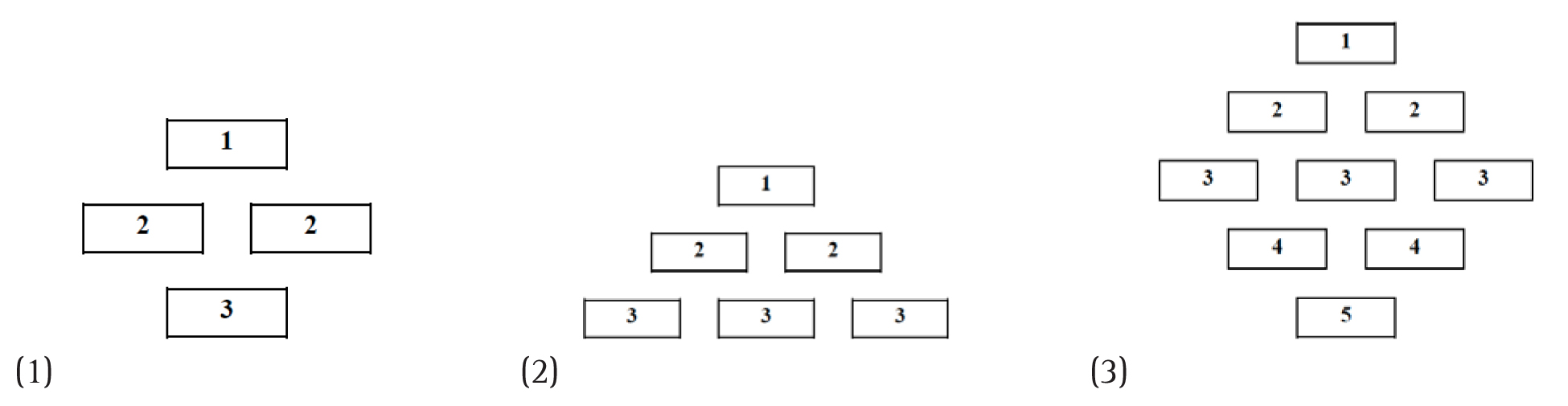

The teacher suggests a model to design a political agenda of goals for the common good. With A4 paper strips marked with numbers as indicated below, he/she introduces model No. 1, a simplified version of the classic “diamond analysis” model (model No. 3).

In the four-goal variant, one goal is given top priority. Two goals are given a second rank, and one goal that is considered to be less important or urgent is given rank 3 (or is omitted altogether – then the teacher removes goal No. 3).

This tight model with three or four goals requires negotiation, as a lot of goals cannot be permitted. On the other hand, fewer goals are easier to implement than an agenda that everybody is happy with, but that is more complicated to handle (the dilemma between inclusion and efficiency). The teacher adds the strips to turn model No. 1 into models Nos. 2 and 3.

The teacher finally points out that all models define only one top priority. So a further, very radical option, would be to define just one goal:

Step 2.4: The students negotiate

The students have several questions to agree on. At the same time, these questions open up different paths to compromise and majority support.

- Which model do we choose – how many goals do we want to include?

- Which goals do we give top priority?

- Could we possibly all agree on just one goal?

- Which goals do we include in our agenda? Goals that support each other, or that exclude each other? (The first option works for efficiency, the second for inclusion.)

- Does the agenda as a whole make sense?

Here careful reasoning and arguing is required. Parties have stronger backing for their goals, but others may have better ideas. It is therefore an open question what goals win the highest support.

The inclusion of goals that exclude each other (e.g. green + conservative) is typical for coalitions between parties or all-party rule. The streamlined model of goals (all defined by one party) is more competitive and conflict oriented. The choice between these models is therefore also a choice of political cultures – ways to handle pluralism in democracy. The teacher observes how the students deal with this issue and decides whether to address it in the reflection lesson.

The students shift the cards on the floor to create their agenda model (to form a diamond or pyramid shape). If several models include the same goals, duplicates are used so that the models can be compared.

The cards are finally stuck on to flipcharts to create posters. These will be used in the following lesson.

Step 2.5: The students vote

At the end of the meeting, the students vote by a show of hands. If they have agreed on one set of goals, a unanimous vote may be expected.

If different models have emerged, the students vote on these models.

In this case the teacher suggests the following voting procedure, which must be decided on (by vote) before the voting on the models begins: if any model wins a majority of over 50%, it is accepted. Otherwise a second vote is cast, this time between the two models with the highest number of votes. To account for abstentions, the model with the highest number of votes is accepted.