Chapter 6 – Understanding political philosophy

Living Democracy » Textbooks » Teaching Democracy » Chapter 6 – Understanding political philosophy

Introduction

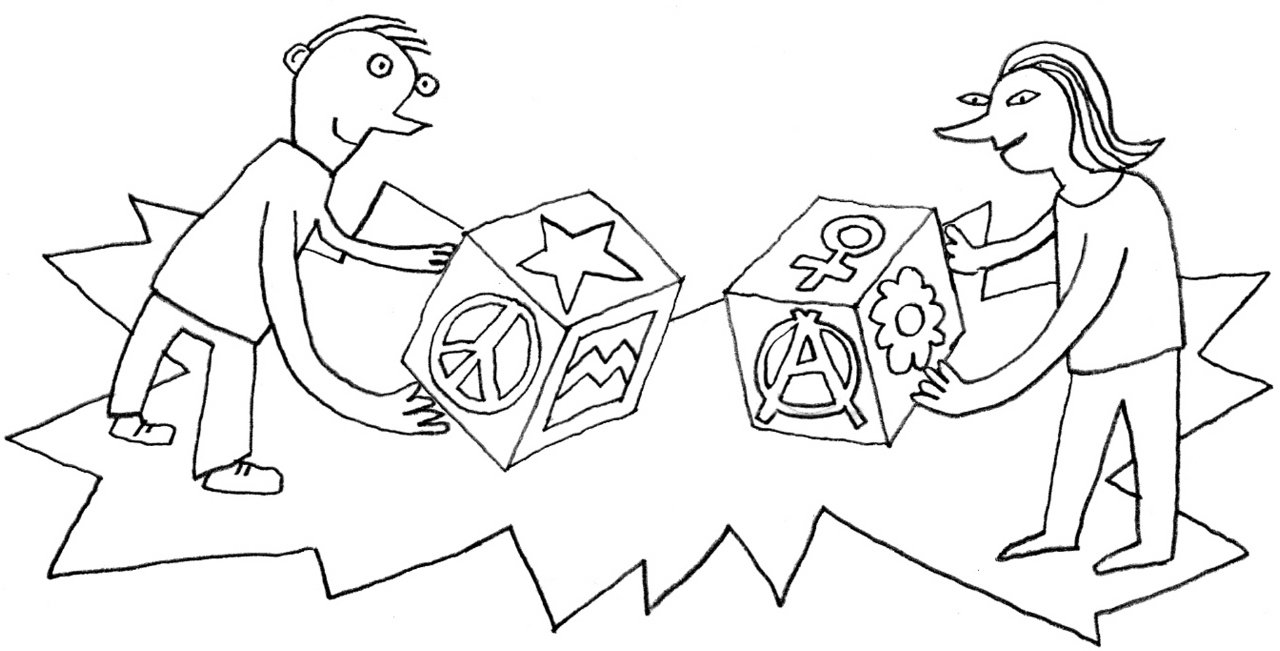

The picture shows a boy and a giri facing each other. They are showing each other a cube with symbols that stand for political philosophies. It is important that they are smiling at each other, as the symbols differ and indicate controversy and disagreement. It is worth while exploring the meaning of the symbols, as far as this is possible. The boy shows the “ban the bomb” symbol, confessing to pacifism. The pentagram could stand for a Socialist point of view, but also for a holistic view of humankind in the universe. The zigzag lines may stand for water, as a symbol for protection of the environment, but the meaning could also be completely different. The girl shows the A-symbol of anarchism. The female gender symbol might stand for a feminist viewpoint. The flower could stand for the protection of the environment, or peace, but the girl may also have given this symbol a different meaning. The young people are making use of human rights – freedom of thought, freedom of expression and equality. There is no authority to decide who is right and who is wrong.

The picture carries an interesting and surprisingly complex message. We combine symbols and concepts in political philosophy to express our ideas and views, but they may be ambivalent or misleading. Therefore we must explain our choices to each other and we must listen carefully. There are many points on which we can agree or disagree. The six symbols suffice to give us an idea of an open, pluralistic society. We should treat each other with respect; then we can have a good argument that harms no one and benefits everyone.

Education for democratic citizenship and human rights (EDC/HRE) integrates two dimensions. The first is related to content. Understanding political philosophy is important in EDC/HRE, as it provides us with a sense of direction and values when we judge issues and take action. We also understand others better.

The second dimension of EDC/HRE refers to the culture of civilised conflict – arguing with a smile, if possible. Such a culture of conflict must be taught in school, by experience and reflection. This can begin at an early age and a lot depends on the example set by teachers and principals. The EDC/HRE teacher should take care to avoid two pitfalls. One is political correctness. It is not the teacher’s task to teach the students any preferred political doctrine, nor should he/she press them to accept his/her personal views. The second is silent neglect, which is a subtle form of oppression. Students should learn to expect and grant mutual attention and response. The teacher should encourage the students to explain their choices so that others can understand them, but they should not be pressed to justify them.

The exercises can be adapted to different age groups and may be used from elementary to upper secondary level.

- Exercise 6.1. - Basic concepts of political thought

Educational objectives The students understand the values that implicitly guide political argument and debate and that some of these values support human...

- Exercise 6.2. - Attitudes to power5

Educational objectives The students can distinguish between concepts of power and their implications for democracy and human rights. The students develop active...

- Exercise 6.3. - If I were a magician

Educational objectives The students are encouraged to create meaningful visions. A person without utopian visions is confined to accepting the status quo....